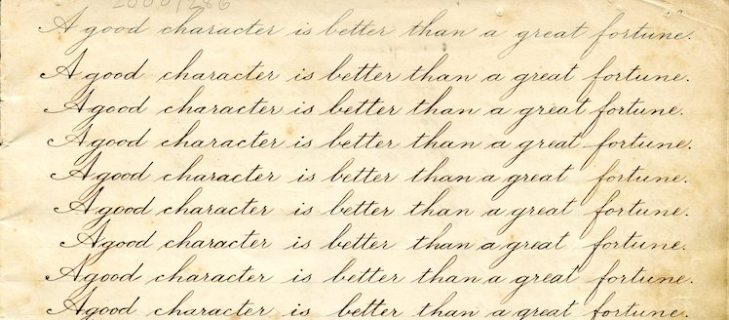

Claude Schumacher’s prized handwriting

Once upon a time … there was time.

Time enough to learn the skills to make things that were both functional and beautiful, objects that could be kept and handed down until we can have them today as a record of that bygone world.

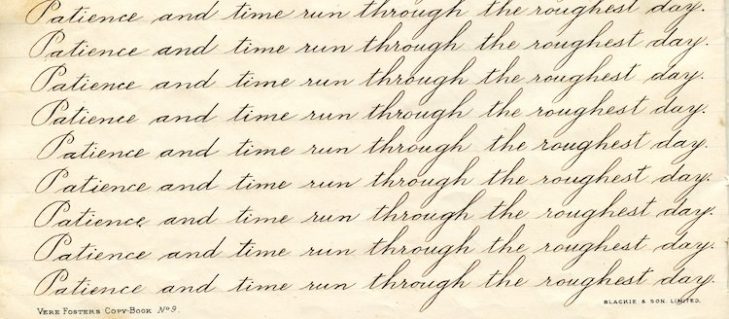

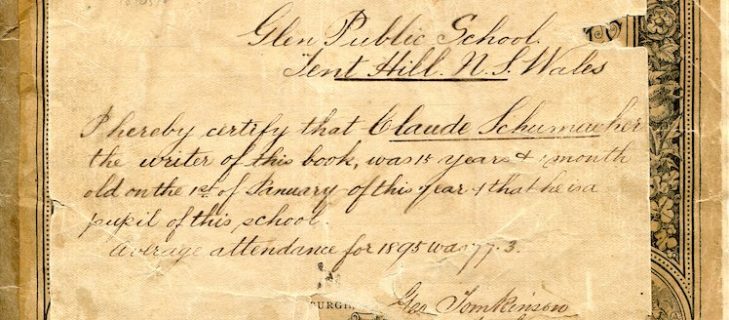

Claude Adolphus Schumacher sat down on the form behind his longtom desk at Tent Hill Public School one day in 1896 and took out his Vere Foster Copybook No. 9 – the highest level for Copperplate round hand – to complete his handwriting. It was his final year at school and he was about to create his greatest scholastic achievement. Tent Hill Public School, also known as Glen Public School, was in the Northern Tablelands district of New South Wales.

His teacher, Mr George Tomkinson, took handwriting very seriously, using his prescribed manuals to teach his students how to write perfectly, because he knew that was how their education would be judged for the rest of their lives.

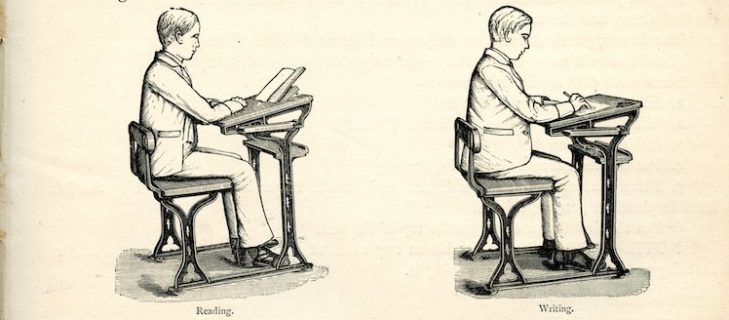

The posture and ‘attitude’ for reading and for handwriting on p.13 in handwriting manual for teachers of juniors. A Manual of Handwriting: How to Give Collective Lessons in Handwriting by F Betteridge. London (1887) (2000-894),

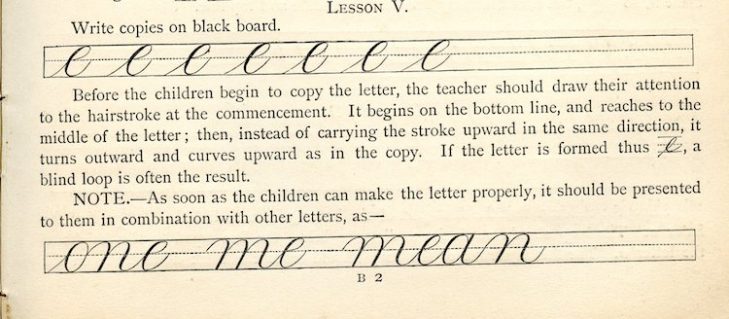

Lesson 5, p.19, in handwriting manual for teachers of juniors. A Manual of Handwriting: How to Give Collective Lessons in Handwriting by F Betteridge. London (1887) (2000-894)

Claude took his work seriously too. He was the fifth boy of the seven sons and two daughters of Katrina Fredereka (Catherine) and John Christian Schumacher who had come out from Germany and Denmark in 1868 to follow the mining boom. They ended up going from Queensland to the Glen Innes tin mining village of Tent Hill, known initially as Vegetable Creek, and from 1882 as Emmaville. There was no family money to cushion Claude’s life … and yet here he still was at school at the age of 15, in Fifth Class, the highest level possible for anyone not going to university.

Someone with good handwriting could go on to do well paid, comfortable work, perhaps even in a bank or post office. Job advertisements usually asked for applications to be handwritten.

First page of Claude Schumacher’s Foster Copy Book No. 9 (2000-286), 1896

Handwriting was a skill, almost an art form, worthy of display. Mr Tomkinson had put Claude’s handwriting forward in last year’s Armidale Show and he had come 2nd out of 13 entries, winning five shillings, missing out on the ten shillings awarded for first prize. The following year Tent Hill Public School children were the ‘principal prize-takers’ in handwriting in Armidale Spring Show due to excellence in style and neatness as reported in The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser on 18 December 1896.

Page from Claude Schumacher’s Foster Copy Book No. 9 (2000-286), 1896

Shows and exhibitions, where knowledge and innovation were spread, and trade opportunities advertised, were hugely popular in the late 19th century, flowing on from the first Great Exhibition in England in 1851.

There were many colonial exhibitions such as Sydney 1879, Brussels 1897 and Paris 1931, intercolonial exhibitions in Melbourne, Brisbane, and Sydney, and Industrial Exhibitions, to showcase the skills and treasures of the British Empire. Crafts on display included woodwork, floristry, metalwork, leatherwork, painting, recitation, needlework, and, of course, handwriting. Categories included handwriting and ornamental pen and ink writing, all worthy of awards.

Cover of Claude Schumacher’s Vere Foster Copy Book No. 9 (2000-286), 1896

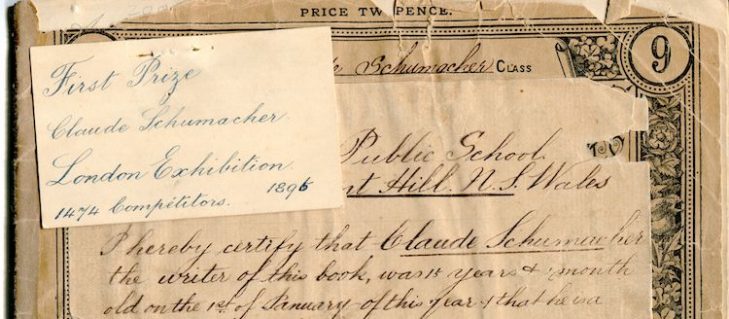

In May 1896 Claude Schumacher submitted his handwriting to be judged at the ‘London Exhibition’ of 1896, perhaps the East London Industrial Exhibition. We know this because we have the book he submitted with Mr Tomkinson’s signature attesting to the fact that Claude had attended an average of 77.3 days each half year in 1895 and Claude’s age of 15 years. With the advent of compulsory schooling from 1880, the law required a minimum attendance of 70 days per half year.

Prize label, in Claude’s handwriting, on the cover of Claude Schumacher Foster Copy Book No. 9 (2000-286), 1896

The label in Claude’s own hand was added later, probably during one of the displays Claude created as an adult. The Deepwater and Emmaville Supplement of the Glen Innes Examiner on 2 December 1937 (p.3) reports on the Emmaville Church of England Bazaar where Claude judged the children’s handwriting competition. There he showed his own perfect work, with the information that he had come first out of 1474 competitors. He must have been proud of this for the rest of his life, even after he had achieved so much more as a prosperous grazier and composer of the New England Waltz in 1908.

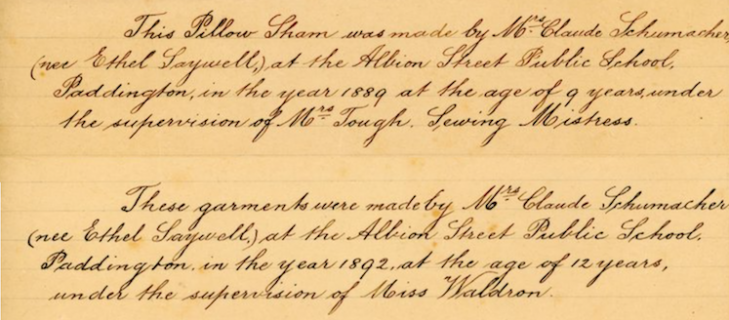

And Ethel, his wife, who was one of the organisers of that 1937 bazaar, as well as many other local CWA events, was also accomplished. She treasured a pillow sham made as a nine year old and needlework garments made as a twelve year old at Albion Street Public School, in Paddington, Sydney, under the supervision of her sewing mistresses, in lessons only available for girls. As with Claude’s handwriting, labels in Claude’s hand were attached to her work and presumably showcased locally in Emmaville.

Needlework might have helped girls of the lower orders get domestic employment, but it was assumed that the real role in life for all the girls was to be a home maker, and being able to make, decorate and repair textiles was essential, even for someone like Ethel from a prosperous family.

Labels in Claude’s handwriting describing his wife, Ethel’s, primary school needlework items, probably for display in local shows. The garments referenced are Needlework petticoat skirt (2000-305), Needlework dress (2000-306), Needlework pinafore (2000-304)

At the age of 13 in 1893 Ethel Josephine Saywell went on to a finishing school. Twenty years later she married Claude, adorned in a “simple but pretty robe of ivory embroidered ninon voile, over ivory satin, trimmed with seed pearls and orange blossoms” as reported in the South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus on 6 June 1913 (p 6). She moved to Emmaville where they raised many sheep and cows and one son, George Frederick. And no doubt wrote beautiful letters and slept upon embroidered pillow slips.

Garments made by Ethel Schumacher (nee Ethel Saywell) at Albion Park Public School at 12 years of age. Needlework petticoat skirt (2000-305), Needlework dress (2000-306)

Endnote

Before objects become significant to a community, they have to mean something to individuals. For all the fifty years that Claude and Ethel Schumacher were married, they treasured the mementoes of what they achieved before they had met. So the month before she died, after ten long years without him, from her flat in La Perouse, Ethel donated Claude’s prize-winning copybook and her prized needlework to the NSW Department of Education who passed it to the NSW Schoolhouse Museum. In the note accompanying the donation, Ethel wrote,

“I was Claude Adolph Schumacher for over fifty years but after he died in Dec 11th 1963 legally I became to my sorry Mrs Ethel Josephine Schumacher. An educated husband and companion is a severe loss. Mrs J Schumacher, 94 years.”

Author

This story was written by Jo Henwood, NSW Schoolhouse Museum facilitator. Jo is also a well known storyteller, guide and museum educator.